We could feel the thin end of the wedge going in against the unions a long way before the miners’ strike.

Say for example there was work on at the weekend, a job taking two days. Normally, I would say to the under-manager, “The men on that job will work right through and finish it, going down the pit at 9 a.m. on Saturday morning, coming back up at 7 p.m. the same night, and doing two shifts in one go; you pay them a double shift for the Sunday and a shift-and-a-half for the Saturday.” He would say yes. But all that was stopped.

Another example was that we used to decide, ourselves, which men would go to a consultative meeting. But then the manager started cutting them all down, telling us who could and who couldn’t go to these meetings.

* * *

At Polmaise, the re-development plan that we had fought for in 1977 was finally agreed to in February 1980. Existing production in the area between the Westermoss fault and the Throsk fault was to be run down and stopped. We were to go for coal on the other side of the Forth river, left behind from Manor Powis colliery which had closed down, and also coal left from when Cowie pit shut down. This meant driving a new mine.

As part of the deal, we had to agree to between 200 and 300 men being transferred while redevelopment took place. As the work in the Westermoss sections came to an end, these men were transferred across to the Longannet complex in Fife and to Kinneil colliery at Bo’ness.

The Coal Board agreed, and it was minuted, that, when the development was complete and we were ready to go back into production, the men transferred out would be the first back to Polmaise.

The redevelopment started and £15.8 million was spent on Polmaise between 1980 and 1983. New buildings were installed on the surface. Two Dosco cutting machines were brought in. The railway line from Polmaise to Stirling was refurbished.

“The work went according to plan and within the allocated budget,” said an economic report on the Scottish coalfield, drawn up during the 1984-1985 strike by two academics, George Kerevan and Richard Savile. “Down to 1983 a total of 16,800 feet of parallel roadways was completed, including drivage work through the Throsk fault. The absenteeism rate was one of the lowest in the UK, there were no industrial stoppages and industrial relations at the pit were described as good.”

But there was a fight in front – about other things, over which we had no control.

* * *

The Thatcher government came to power in May 1979, and in less than two years the miners came face-to-face with them – in February 1981, when the Coal Board announced a plan to close 23 pits. A strike began on February 16th at one of the Welsh pits which was on the closure list. It spread rapidly and Polmaise was one of the first Scottish pits out.

The NUM Scottish area vice-president, George Bolton, had phoned me and told me the executive wanted Polmaise to be idle. But we already knew ourselves that we would be idle. We didn’t need to be told.

The press came to the pit, wanting to know why we were out on strike. We kidded them on and told them a bus-load of Welshmen had come up and knocked us idle during the night shift. This rumour spread so far that we even had a call from BBC Radio Wales. But in fact there were no Welsh miners in sight!

This all happened on a Tuesday. Some pits didn’t go out on strike; they were waiting until the Saturday, when they held their branch meetings. But by that time Thatcher had drawn her wings in, the proposed closure plan had been withdrawn, and the pits were all back at work.

It was no coincidence that Polmaise was one of the first pits out. We had a reputation for militancy which went back to before the war. We didn’t need anyone to come to convince us it was right to go on strike. We could discuss it at local level, in the miners’ welfare, in the pit yard, or in the union office (or union box, as we called it). In fact I cannot remember an executive Committee member ever coming to Polmaise to talk about strike action: it was always left to the local delegate, branch committee, and membership.

The union box at Polmaise was open to any member. At times you couldn’t get in, because it was full of men sitting, getting themselves involved – whether they were on the committee or not. There are some pits where miners only go in the union box if they have a case to be dealt with, but Polmaise was not one of those. The miners used to come in, listen to different arguments about problems at the pit, and have a blether and a cup of tea. We always had a big teapot full of strong tea.

When I took over as delegate, there were 600 men in the pit – and in a certain sense you could say, there were 600 delegates. Everybody knew what was going on, they could relay the message. It all made the job very easy.

Plus I had a good committee to work with. If I was away at a meeting, there were those like Jock Perrie (our former minutes secretary, who died after the strike), James Armitage the branch secretary, or George Goodwillie the branch chairman, who could keep an eye on things. This was why it was so sad when Polmaise closed: it was a village pit, one that you actually looked forward to going to. The involvement was great, it was a viable unit and everything was working smooth.

* * *

In June 1982, Arthur Scargill was elected national president of the NUM with 70.4 per cent of the votes. In September that year, the NUM national conference at Inverness decided a policy of all-out opposition to pit closures, together with demands for a four-day week, retirement at 55, and wage increases for all grades with a £115-a-week minimum.

In October, there was a national NUM ballot for strike action, against pit closures and for a 31-per-cent wage increase. The theme of the papers at that time was that in some of the English pits large amounts of bonus would be lost if there was a strike. I think this sort of propaganda swung things against the proposal for strike action – and while the majority of Scottish miners (69 per cent) voted for strike action, on a national scale the ballot was lost.

Polmaise often had a 98-per-cent vote in favour of strike action not just in one ballot, but in practically every ballot we took. Some of our senior NUM officials in the Scottish area didn’t think results of this kind were feasible! But the reason for them was that we were a village pit and the solidarity was there.

* * *

Having decided to fight all closures (except on grounds of exhaustion) the NUM didn’t have to wait very long for one. In October 1982 the Coal Board announced that Kinneil pit at Bo’ness, west Lothian, was to close. The Kinneil men were promised full backing from the NUM and from the Labour Party national conference.

On Monday December 21st 1982, twelve Kinneil men, who became known as the “Dirty Dozen”, began a five-day underground sit-in. They came to the surface on Christmas Day. Then a branch meeting was held and it was decided to picket all the Scottish pits, asking them to strike in support of Kinneil.

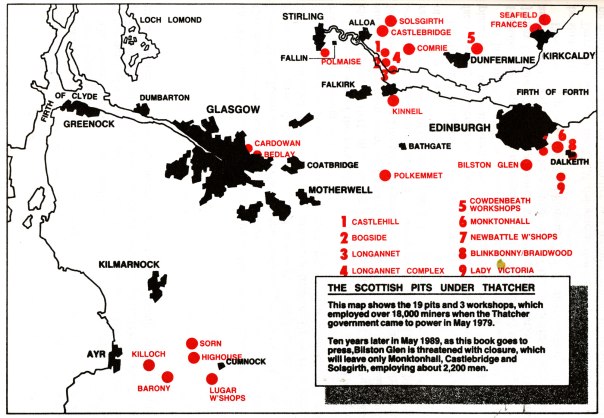

The picketing began on December 27th. Cardowan, Polmaise, Bogside, Sorn, Killoch and Comrie pits walked out straight away. Castlehill followed on the back shift. Highouse said they would strike at the end of the holidays. The Kinneil pickets got only a partial response at Solsgirth, Monktonhall and Bilston Glen. There were no pickets at Seafield or Frances, but one-third of the Frances day shift went home anyway.

On the Tuesday morning, December 28th, a conference of NUM secretaries and delegates from all the Scottish pits was held. Present were five representatives from the Lewis Merthyr pit in Wales, who also  faced the threat of closure and who were up in Scotland looking for support. The Scottish area NUM also allowed some of the Kinneil miners to come into the meeting, without taking any part.

faced the threat of closure and who were up in Scotland looking for support. The Scottish area NUM also allowed some of the Kinneil miners to come into the meeting, without taking any part.

Mick McGahey [the Scottish NUM president] started off, with a report from a special [Scottish NUM] executive committee meeting held the previous day. At the executive meeting, he explained, “every member had reported on the position in their own and adjacent collieries, when it had been clearly demonstrated that the hearts and minds of the Scottish miners had not been won for action on Kinneil” (quoted from the official NUM minutes). McGahey continued: “Reluctantly, therefore, the executive Committee had decided unanimously to call off action in support of Kinneil, where limited action had taken place, and to call for the resumption of normal working, which in effect meant the loss of Kinneil colliery.” He opposed further strike action on the basis that “fragmentation throughout the coalfield could result in battles being lost in future”.

It was not true that the hearts and minds of the miners had not been won for Kinneil. I know for example that there was never an EC member at Polmaise to discuss the Kinneil situation. The only person who came and spoke to us was Jimmy McCallum, the Kinneil NUM delegate. We told him that the Polmaise men were backing him to a man, 100 per cent, and we came out on strike.

On the morning of this meeting, myself and Jim Armitage, the Polmaise branch secretary, had gone up to Edinburgh in the car with the Castlehill delegate. We had been talking in the car about the need to do something to back Kinneil colliery, and the Castlehill delegate agreed. The miners were stopping work for Hogmanay [traditional Scottish word for New Year’s Eve] the next day. And his version of it was that, once the holidays were by, we would all be on strike for Kinneil. And yet when McGahey got up and made his statement that Kinneil was effectively lost, the Castlehill delegate jumped up and agreed with him straight away.

“Fragmentation in the coalfield now could affect the struggles in future,” said the Castlehill delegate, and while he and other branch officials at Castlehill had fully supported the Kinneil miners in their stand, there was, in view of the situation which had now developed, no alternative but to support the executive committee recommendation. The reason they constantly gave for not supporting Kinneil was “fragmentation” in the branches or “fragmentation” in the coalfield. The delegate from Bilston Glen said: “Unfortunately, there has not been a response and to do other than accept the executive committee’s recommendation would cause fragmentation, leading to a lengthy battle which would involve miner fighting miner and which must be avoided.”

There were other similar statements. One executive committee member said that while his own colliery, Bogside, had been idle, he had not been able to come forward with an alternative at the special meeting of the executive committee, hence the reason why he had voted along with the executive committee in favour of the recommendation proposed by the Scottish area officials. His own pit was idle – and yet he voted to shut Kinneil!

Another executive member said that to have rejected the Scottish area officials’ recommendation would have led to further chaos through the coalfield, and there had been no alternative but to accept this recommendation.

These people have a lot to answer for.

The minutes quote Bill Sneddon, the Kinneil SCEBTA delegate who led the underground sit-in: “He had witnessed events in the Scottish coalfield, events which he had never dreamed would occur, where men were running over the top of each other, where certain delegates had pulled pickets off buses and had not been allowed to address the men …”

Jim McCallum, with Sneddon and others at the back of him urging him on, moved rejection of the executive committee recommendation to let Kinneil go. This is what the minutes say about my own statement: “Mr McCormack (Fallin) stated that in his opinion the executive committee had dragged their feet. They should be prepared to explain the reasons why they could not win support for Kinneil Colliery, the recommendation now before conference being a complete reversal of previous decisions taken by the Union. His colliery was totally idle and he had hoped that similar support would be forthcoming for the men at Kinneil at today’s conference.”

At the end of the conference, the NUM delegates voted 12-7 to support the executive, that is, to refuse support to Kinneil. The Scottish Colliery Engineers, Boilermakers and Tradesmen’s Association (SCEBTA) delegates also refused support for Kinneil by 8 votes to 6. Some delegates left the hall to shouts of “traitor” and “scab” from Kinneil pickets outside.

This was the first time we began to realise there was something wrong with the Scottish NUM’s policy. At that time, we didn’t know what was going on between them and the Coal Board – but now, any of the men who worked at Kinneil would tell you that there were dirty tricks. They came to believe that the NUM area leadership was working hand-in-hand with the Coal Board regarding the closure.

If we knew then what we know now, we would have taken a much harder line against these sort of leaders. When I first worked at the pit, before I was involved in the union, I thought the people in the leadership of the union were genuine guys – but once you saw what happened at Kinneil, Sorn, and these other pits, you began to think otherwise.

* * *

Kinneil turned out to be the first of a series of closures. On April 14th 1983 the Coal Board announced that they intended to close Sorn, a small colliery in Ayrshire. The membership voted by 35 to 7 to fight for their jobs.

Alex Mills, the delegate there, was a good man, and a continuous thorn in the side of the Coal Board and union leadership alike.

But Sorn – and Highouse colliery nearby, which was closed shortly afterwards – did not get any support. It was as if they were not there. No recommendation came from the Scottish executive to fight for either pit.

Back to contents *** Go to chapter 3

Back to contents *** Go to chapter 3